There is no doubt that forced isolation involves a great cost, both at a personal and societal level. Already in the 4th century B.C., Aristotle had the essential insight that our nature as human beings is social. In Genesis, we read that “it is not good for the man to be alone” (Gen 2:18). In COVID times, the greatest prison that we live in is the one of separation from family and friends.

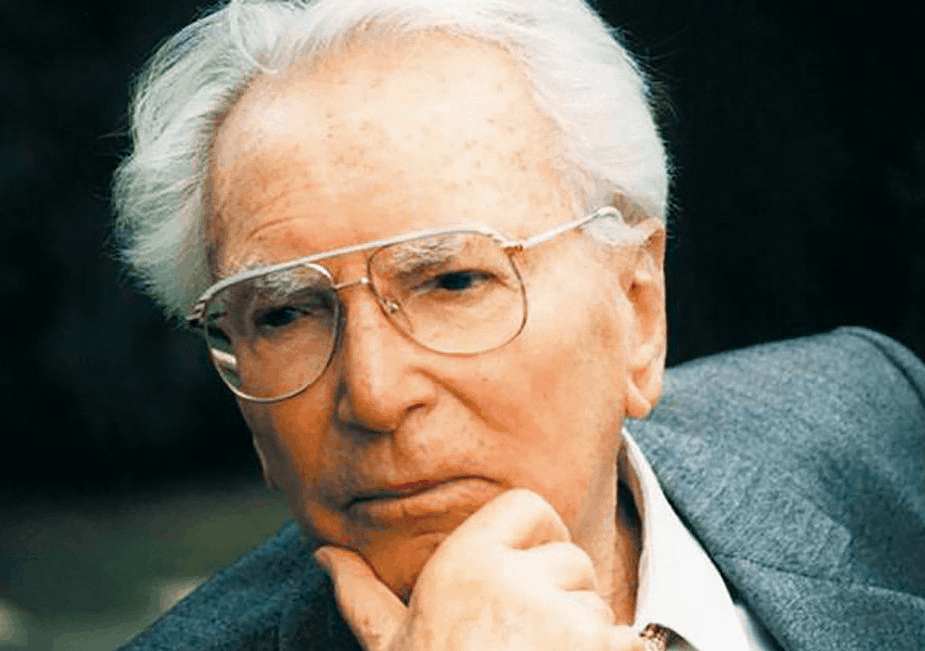

Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist and philosopher who wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, indicates some useful signposts to help us cross this strange and unexpected land of quarantine. His whole family was wiped out in the Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Having lived in the camps, he understood that any attempt to restore people’s inner strength had first to succeed in showing them some future goal.

“Nietzsche’s words, ‘He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how,’ ” can act as a guiding motto, says Frankl. In other words, we can begin to ascend from the rubble if we try recapturing the meaning of our existence.

Making sense of meaning

But what is the meaning Frankl is speaking about?

According to him, there are three primary ways we can discover a why to live for. These are by:

1. Creating a work or doing a deed

2. Experiencing something or encountering someone

3. Taking a particular attitude toward unavoidable suffering.

These are the often-hidden roots in recapturing who we are as human persons.

How can being creative answer the question, “Who am I?” We have to realize that we have not only reasoning capabilities, but a “doer” nature as well. My mind also evolves through what I am “doing” as well as through “knowing.”

Frankl, for example, remarks on the experience of “give-up-itis” among some prisoners who lost all hope in their difficult situation and simply gave up living. They “un-became” who they were as persons. He explains how “nothing … could induce them to change their minds … Meaning, orientation had subsided and vanished from them.”

A first way of creatively recovering meaning, especially during these times of crisis, is evident in the examples of medics, business people, and even artists who search for new ways in providing for us and communicating to our souls.

During the lockdown, there were wonderful news reports of musicians and singers putting on impromptu performances from their home balconies for their families and neighbors. This is not perhaps so surprising, since an artist, after all, cannot but be who he or she is.

Speaking about art, Pope Francis says that it has “in itself a salvific dimension,” being open to everyone and “offering consolation and hope to each one.” Art’s creativity “knows how to speak to persons.”

Yet our normal human deeds also have this capacity. In creating a work or doing a deed, we transform not just external objects or our environment, but also our inner selves. In an amazing way, we become who we are in human action, and this is what gives work its dignity.

Just as we have the capacity to “know the good,” we equally have the power to “be” and “do” good. In doing the right deed, we become good.

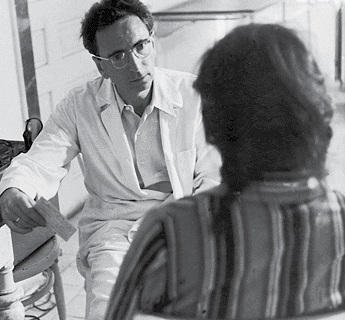

For Frankl, the second way to discover the meaning of our existence is by “experiencing something or encountering someone.” The “something” he is speaking of is not an object or a possession.

He explains how, in experiencing “goodness, truth and beauty,” we can grasp significant meaning. Traditionally, “goodness, truth and beauty” are called the “transcendentals.” Each of the transcendentals goes beyond the limitations of space and time and is rooted in being.

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread,” Frankl remarks. This is the face-to-face encounter with goodness evidenced in the lives of others, an experience that cannot be taken away from us. It is “the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

In the pandemic, we too can recall the many heroic stories of goodness and kindness lived by nurses, doctors, chaplains, and hospital staff, accompanying patients who are dying on their own without friends or relatives at their bedsides.

Frankl believes that it is also in encountering another person that we can recapture what it is to be. This is love not in the abstract; it means to love “someone.” He says we come to meaning “by experiencing another human being in his very uniqueness — by loving him.” Frankl explains how “love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality. He says:

“No one can become fully aware of the very essence of another human being unless he loves him. By his love, he is enabled to see the essential traits and features in the beloved person; and even more, he sees that which is potential in him, which is not yet actualized. Furthermore, by his love, the loving person enables the beloved person to actualize these potentialities…”

I love, therefore, I am

If Descartes said, “I think, therefore, I am,” we can almost say, “I love, therefore, I am.” We don’t have to be physically present to do this. In today’s digital world, there are various ways of communicating our practical love and care for others.

Frankl describes how in the concentration camps he discovered “how a man who has nothing left in this world may still know bliss.” There’s the discovery that “love goes far beyond the physical person of the beloved. It finds its deeper meaning in his spiritual being, his inner self.”

We are reminded here perhaps of St. Augustine’s experience when he said, “Late have I loved you, beauty so ancient and so new: late have I loved you. And see, you were within, and I was in the external world and sought you there … You were with me, and I was not with you.”

Thirdly, it is in the attitude that we take in the face of unavoidable suffering that we can recapture our meaning as persons. In 5th century B.C. Greek tragedy, they spoke of the principle of ‘pathei mathos,’ that is, the fact that real wisdom often comes through suffering.

Frankl says that once we discover that external circumstances cannot be changed, “what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential at its best, which is to transform a personal tragedy into a triumph, to turn one’s predicament into a human achievement. When we are no longer able to change a situation … we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Furthermore, Frankl freely admits that there are situations in which we are cut off from the opportunity “to do one’s work or to enjoy one’s life.” There is the “unavoidability of suffering,” but in accepting this bravely, “life has a meaning up to the last moment, and it retains this meaning literally to the end.”

This is an example of a loving love that goes beyond limitations. Chiara Lubich says this hidden way of living is a “person,” namely, Jesus, forsaken on the cross. He is the very reason “why persons can be fulfilled, going beyond any limitation.”

Fr. John McNerney

(Living City, USA)

Fr. McNerney, Ph.D. is the Michael Novak Distinguished Scholar at the Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship in the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.