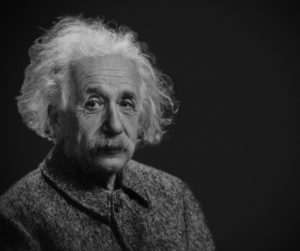

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was born in Ulm, Germany on March 14, 1879, to Jewish parents. In 1880, after his father’s business went through a crisis, the family moved to Munich, where Einstein went to school. At a very young age, he studied violin and algebra. He read scientific books, and at 15 he began teaching himself calculus.

As he was intellectually mature for his age, he developed a healthy self-confidence and was suspicious of and rebellious toward any established authority – an attitude that remained with him throughout his life. In 1896, Einstein applied to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, where he decided to dedicate himself definitively to physics. He spent long hours in the university lab, “fascinated by direct contact with experience.”

The rest of his time he spent at home studying the works of physicists like Ludwig Boltzmann, Gustav Kirchhoff, Hermann von Helmholtz, and Heinrich Hertz, developing a robust background in theoretical physics and a clear understanding of the open questions posed by various fields of physics.

During this time, he also read the works of such philosophers as Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, Immanuel Kant and others such as Ernst Mach, who investigated the origins, nature, methods, and limits of human knowledge. The insights gleaned from them were to have a lasting impact on him.

Einstein graduated in 1900. Two years later, he received his Swiss citizenship and found work at the Patent Office of Bern. The year that would be a turning point for him was 1905. That year, as a young outsider still not part of the academic community, he was able to publish a few articles in the Annalen der Physik (Annals of Physics).

These articles would revolutionize the science of physics and turn people’s overall view of the world upside down. One of these articles included Einstein’s proposal of a new theory of relativity, based upon two principles: that the laws of physics do not change, when we shift from an inertial frame of reference to another, and that the velocity of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers and is the highest velocity attainable.

In the same articles, Einstein also offered an interpretation of the photoelectric effect that would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1921. In another, the formula of the mass-energy equivalent, E=mc2, appeared and was destined to become the most celebrated equation in the realm of physics. The 1905 articles had a decisive effect on Einstein’s career.

In the same articles, Einstein also offered an interpretation of the photoelectric effect that would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1921. In another, the formula of the mass-energy equivalent, E=mc2, appeared and was destined to become the most celebrated equation in the realm of physics. The 1905 articles had a decisive effect on Einstein’s career.

Already a professor at the University of Bern, he was named associate professor in Zurich in 1909. In 1914, urged by physicists Max Planck and Walther Nernst, he accepted an offer at the University of Berlin, where he could dedicate his energy completely to research without the obligation of teaching.

Ever since 1907, he had already been developing an ambitious project: writing down his theory of relativity in order to also understand gravity. This undertaking required sophisticated mathematical elements (such as non-Euclidean shapes and absolute differential calculus), which Einstein would acquire with perseverance and an extraordinary ability to work.

On November 25, 1915, Einstein’s gravitational field equations were finally made public, and so the theory of general relativity came to life. In it, “space-time” is considered a deformed geometrical shape, curved by the presence of matter, energy, and mass.

Einstein’s equations offered the exact relationship between the total curve and the quantity of matter necessary to produce it. They were able to explain the phenomenon that Newtonian mechanics could not, such as the anomaly of Mercury’s orbit.

But the overwhelming evidence came in 1919 when during a total solar eclipse, Sir Arthur Eddington was able to “photograph” the deflection of the light coming from the stars, produced by the curvature of the gravitational field around the sun.

The announcement of this evoked strong reactions with exclamations like, “Newton has been ousted from his pedestal.” As one writer put it, the universe “unexpectedly” became “a living structure, mobile, and plastic, full of trenches and tunnels and steep slopes.” And Albert unexpectedly became “the famous Dr. Einstein.”

The announcement of this evoked strong reactions with exclamations like, “Newton has been ousted from his pedestal.” As one writer put it, the universe “unexpectedly” became “a living structure, mobile, and plastic, full of trenches and tunnels and steep slopes.” And Albert unexpectedly became “the famous Dr. Einstein.”

In his autobiography, Einstein himself wrote that “the surprising thing about the world is that it is understandable.” He confessed that “Experience naturally remains the only criteria in order to apply mathematical constructions in physics, but it is through mathematics that one finds the truly originating principle. From a certain point of view, I recognize that pure thought is capable of grasping reality, as was thought in ancient times.”

His theory was crucial to the emergence of modern scientific cosmology and the elaboration of the Big Bang Theory. In 1933, as Adolf Hitler came to power, he decided not to return to Germany. He obtained a university post at Princeton University, where he would enrich his research in original and fruitful ways. He remained at Princeton until his death on April 18, 1955.